With continuing and growing protests over police brutality, racial and gender inequality, and various relevant activist groups, I am made even more aware of the disparity that still exists in the publishing world. Yes, things are getting a little better and more inclusive, ever so slowly. At times, it feels as if we take one small step forward and three or four giant steps back. But it is encouraging to see that there are more women and authors of color being published and recognized for their contributions. NK Jemisin, for example, was the first Black woman to win the Hugo in 2016, and she proceeded to win the prestigious science-fiction/ fantasy (SFF) award for the next three years in a row.

I mention that Jemisin won the Hugo for three years running not because she is an awesome writer of speculative fiction (though she is). Rather, I mention it because the Hugo Awards had been nearly taken over by an alt-right subculture that wanted to silence the rising prominence of women and other marginalized groups within the SFF (Romano. 2018). The publishing industry has been working towards creating more diversity across all genres, not just SFF. But within the SFF community, a few things happened to really help kickstart a better approach to publishing and fan communities. The first of these was “Racefail,” a year-long discussion about the lack of diversity and the overwhelming dominance of white colonialism within the SFF culture. Romano (2018) notes that “the conversations around Racefail resulted in an emerging awareness of the need to not only embrace the writing of women and people of color, but also to make the community a safer space for all writers” (para 7). Racefail led to a growth of diversity and a lessening of gatekeeping on who was allowed to participate in the SFF culture.

It is important here to note that the Hugo Awards are voted on by members of the annual World Science Fiction Society (WorldCon) rather than by a voting committee, and anyone can become a WorldCon member. Doing the voting in this way effectively makes the Hugos a crowdsourced event and it also helps to show changing trends within the SFF community. Unfortunately, it also can provide a space for people to try to game the system. Most notably within the SFF community, two subgroups have tried for years to influence the Hugo Awards by getting their followers within the WorldCon community to vote en masse for certain writers. These groups, called the Sad Puppies and the Rabid Puppies (no, really), formed when author Theodore Beale “Vox Day” was banned from the professional Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA) after he made posts referring to NK Jemisin in truly awful, racist ways. Another author, Larry Correia, made a blog post in which he whined that his book wasn’t getting any Hugo nominations and asked that all his readers vote for him. Correia went on to establish the Sad Puppies, and Vox Day followed suit and made the Rabid Puppies. Vox Day has since been recognized as a leader within the alt-right movement. The Puppies went on to get ultra-conservative voting groups to vote for authors they had approved to prevent more diverse authors from making it to the Hugo list.

The first year the Puppies were active, they got 107 out of 127 authors on the initial Hugo voting ballot. So, they were right that the Hugos could be pretty easily manipulated. However, turnabout is fair play, and it seems the SFF community in general loves a good bit of revenge. Things backfired brilliantly when, while attempting to make the Hugos into a joke, the Puppies nominated Chuck Tingle, an erotic fantasy author, to the list. Tingle was well aware of what the Puppies were trying to do, so he created a page on his website to celebrate his Hugo nomination, and then he directed his audience to the sites and books of the women the Puppies were trying to block from being nominated. Similar actions over the past few years have been the way in which the Puppies and other groups like them are being stymied. Many times, authors will simply withdraw their name from consideration if they were nominated because of actions from the Puppies. Another common practice is that voters choose “no award” instead of a “Puppy approved” nominee. For the past couple years, Sad and Rabid Puppies have seen their influence drop as the Hugos, and the SFF community as a whole, have sided with the voices of the marginalized. As Jemisin said in her acceptance speech for her third Hugo award (YES, girl!), “SFF is a microcosm of the wider world, in no way rarefied from the world’s pettiness or prejudice. … I look to science fiction and fantasy as the aspirational drive of the Zeitgeist: we creators are the engineers of possibility. And as this genre finally, however grudgingly, acknowledges that the dreams of the marginalized matter and that all of us have a future, so will go the world” (Cadenhead, 2018, 2:33).

Below are just a few SFF books written by a variety of marginalized voices that are all well worth the read. If you have other recommendations, whether in SFF or any other genre, for novels by marginalized individuals, please let me know!

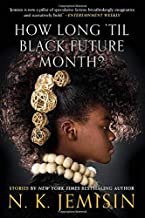

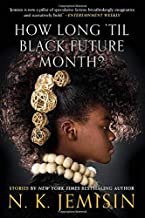

NK Jemisin – I can’t start a list for an article like this without telling you to go read Jemisin’s Hugo-winning Broken Earth trilogy posthaste. You will not be disappointed! She also has a fabulous book of short stories out, When Will It Be Black Future Month?

NK Jemisin – I can’t start a list for an article like this without telling you to go read Jemisin’s Hugo-winning Broken Earth trilogy posthaste. You will not be disappointed! She also has a fabulous book of short stories out, When Will It Be Black Future Month?

Nalo Hopkinson – I’ve read several of her books, most recently The Salt Roads and Brown Girl in the Ring. Both are excellent works of speculative fiction that explore privilege, social status, and race in beautifully rendered narratives, heavy with Afro-Caribbean cultural influences.

Nalo Hopkinson – I’ve read several of her books, most recently The Salt Roads and Brown Girl in the Ring. Both are excellent works of speculative fiction that explore privilege, social status, and race in beautifully rendered narratives, heavy with Afro-Caribbean cultural influences.

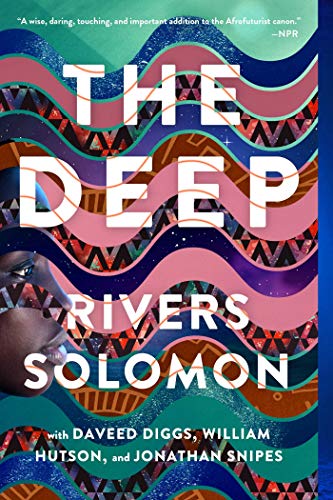

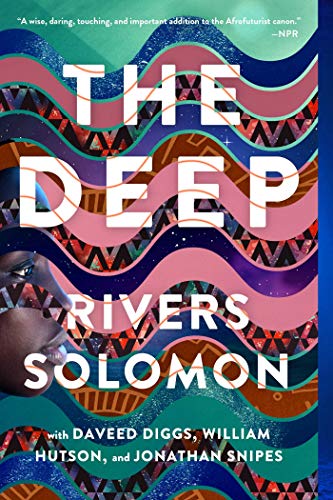

Rivers Solomon – An Unkindness of Ghosts is set on a generational spaceship that has been divided into social classes correspondent with where one’s living quarters are situated. They have a second book, The Deep, about water-dwelling descendants of African slave women who were thrown overboard while crossing the Middle Passage. Extra diversity info: Rivers Solomon identifies as nonbinary and on the spectrum.

Rivers Solomon – An Unkindness of Ghosts is set on a generational spaceship that has been divided into social classes correspondent with where one’s living quarters are situated. They have a second book, The Deep, about water-dwelling descendants of African slave women who were thrown overboard while crossing the Middle Passage. Extra diversity info: Rivers Solomon identifies as nonbinary and on the spectrum.

Octavia E. Butler – one of the queens of “traditional” SFF, Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, beginning with Dawn, is the story of Lilith, a woman cryogenically frozen by the Oankali. These aliens survive by genetically merging with other species. They wake Lilith up when Earth becomes habitable again and Lilith has to decide if she will support the Oankali’s methods of saving humanity or if she will side with humans, even if it means extinction.

Roxane Gay – OK, so she wrote Black Panther: World of Wakanda and is well respected in the SFF community. But I really want everyone to read Gay’s memoir, Hunger, which explores topics such as sex, food, body image, and health through the lens of her own personal experiences. Also, her book of essays, Bad Feminist, is a must-read for everyone, whether you identify as feminist or not.

Karen Lord – her book The Best of All Possible Worlds explores topics ranging from technology to sexuality to injustices by telling the story of the Sadiri, whose home world was obliterated by another species.

Walter Mosley – Mosley is probably best known for his Easy Rawlins hard-boiled mystery series, and that is indeed a delightful series to read. However, Futureland is a collection of nine short stories about a future society divided by technology and wealth. Kind of like society today.

Victor LaValle – LaValle’s novel The Ballad of Black Tom takes Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos for a spin by narrating the tale from the perspective of a Black man working for the protagonist, Robert Suydam.

Nisi Shawl – Everfair is Victorian! Afro! Steampunk! It speculates on what the world would look like if the tribes of the Congo had developed steam power before the Belgians colonized their land.

References

Cadenhead, R.. (2018, August 19). N.K. Jemisin’s 2018 Hugo Award Best Novel acceptance speech [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8lFybhRxoVM.

Romano, A. (2018, August 21). “The Hugo Awards just made history, and defied alt-right extremists in the process.” Vox.com, retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2018/8/21/17763260/n-k-jemisin-hugo-awards-broken-earth-sad-puppies.

nside Out and Back Again

nside Out and Back Again

NK Jemisin – I can’t start a list for an article like this without telling you to go read Jemisin’s Hugo-winning Broken Earth trilogy posthaste. You will not be disappointed! She also has a fabulous book of short stories out, When Will It Be Black Future Month?

NK Jemisin – I can’t start a list for an article like this without telling you to go read Jemisin’s Hugo-winning Broken Earth trilogy posthaste. You will not be disappointed! She also has a fabulous book of short stories out, When Will It Be Black Future Month? Nalo Hopkinson – I’ve read several of her books, most recently The Salt Roads and Brown Girl in the Ring. Both are excellent works of speculative fiction that explore privilege, social status, and race in beautifully rendered narratives, heavy with Afro-Caribbean cultural influences.

Nalo Hopkinson – I’ve read several of her books, most recently The Salt Roads and Brown Girl in the Ring. Both are excellent works of speculative fiction that explore privilege, social status, and race in beautifully rendered narratives, heavy with Afro-Caribbean cultural influences. Rivers Solomon – An Unkindness of Ghosts is set on a generational spaceship that has been divided into social classes correspondent with where one’s living quarters are situated. They have a second book, The Deep, about water-dwelling descendants of African slave women who were thrown overboard while crossing the Middle Passage. Extra diversity info: Rivers Solomon identifies as nonbinary and on the spectrum.

Rivers Solomon – An Unkindness of Ghosts is set on a generational spaceship that has been divided into social classes correspondent with where one’s living quarters are situated. They have a second book, The Deep, about water-dwelling descendants of African slave women who were thrown overboard while crossing the Middle Passage. Extra diversity info: Rivers Solomon identifies as nonbinary and on the spectrum.