Girls Burn Brighter: A Novel

Girls Burn Brighter: A Novel by Balli Kaur Jaswal

I read it as a: hardback

Source: my own collection

Length: 307 pp

Publisher: Flatiron Books

Year: 2018

**This review will very much have all the spoilers. Consider yourselves warned.**

In Girls Burn Brighter, two young women form a strong friendship through the harshest adversities. Poornima is the daughter of a sari weaver. Her family is fairly poor but they have enough to eat and to hire Savitha to help with weaving after Poornima’s mother dies. Savitha is from a poor family, so poor they have to resort to digging through the landfill for food. When the two women meet, they form a deep bond, one of those once in a lifetime friendships. When Poornima’s father begins arranging her marriage, Savitha encourages her to hold out for a man who is young and kind with a bunch of good sisters. A match is finally made and Poornima’s marriage is set. Then, a cruel act drives Savitha away on the eve of Poornima’s marriage and each woman embarks on a new part of life, alone. Eventually, another horrific act drives Poornima away from her marriage and off to seek Savitha, a journey that takes her from her home village to Mumbai to Dubai and eventually to Seattle.

The title itself made me nervous when I first started reading and began to understand more about the plot (I rarely read more than the blurb when I pick a book, and I never read reviews before I read a book, so I stay spoiler-free). I had worried that someone was going to get burnt to death because she’s a girl. However, I liked that it served more as a discussion on the strength of women even through adversity. After Poornima’s husband and MIL burnt her with oil, she realized she was supposed to fade into obscurity and invisibility. Instead, her inner light burnt brighter and she was more her own person, and managed to carve out a life for herself, even if it wasn’t what she might have wanted. It was her own and she took no shit from anyone. Savitha had a brighter light at first, which was utterly extinguished by her rape and subsequent capture by the brothel owners, but she eventually remembered it and saved herself.

I think that the relationship each woman had with her own father was a major factor in how each handled her circumstances. Savitha had a good and loving relationship with her father, and when she encountered abuse and horrors, she was unprepared to deal with it. Conversely, Poornima hated her father, who was an abusive drunk, and when horrible things happened to her, she adapted and survived and did what she needed to in order to get out. She never seemed surprised or terribly hurt when people were awful, which is terrible in itself. It seems like a fucked up way of learning how to deal with real life, like some kind of Grey’s Anatomy version of parenting – preparation through emotional, mental, and physical abuse and neglect.

Girls Burn Brighter was a shocking novel to read on multiple levels. Strangely, I was startled when I realized it was set in the current time. There were references to some years, one of them being 2001, and I was simply amazed, I assume because of my ignorance about the culture, that it was in a modern setting. It just felt like something that would have happened in an earlier time, the crushing poverty, the cruelty, effectively selling your children into slavery. Things like that aren’t supposed to happen now. But of course they do, which is a central theme of the novel. The way Poornima and Savitha were handled in this novel was really eye-opening for me, not because I am unaware that women deal with things like domestic abuse, rape, or sex trafficking every day, but because the story put a face to these issues. Why else read but to gain a deeper understanding, empathy, and compassion for people whose situations in life are totally incomprehensible to us? I can’t fathom being drugged and taken to a brothel, being forcibly addicted to heroine, then forced to go through withdrawal, then sold into sex trafficking. But it happens. I can’t imagine living like Poornima or Savitha, having an arranged marriage, having a man who is so insecure with his masculinity that he feels it necessary to scar me for life by holding me down and pouring boiling oil on my face. But it happens. Actually, the conflict between Poornima and her husband, when she suggests she isn’t barren but perhaps he is, reminds me of the story Margaret Atwood tells about her male friend and the group of women: She asked him why men are afraid of women and he says it’s because men are afraid women will laugh at them. She asked a group of women why they are afraid of men and they said it’s because they’re afraid the men will kill them. There was so much of that woven throughout this narrative, of small, insecure men feeling threatened by women and so they hurt them to keep them under control or in terror.

Mohan might have been a somewhat sympathetic character since I think he didn’t want to be a part of his father’s “empire.” But since he didn’t actually do anything to stop it, and helped to bring girls to America to further the empire, I found him simply to be pathetic rather than sympathetic. He was a revolting figure, who oddly added rather a lot to the story. He was conflicted about what was happening, but too weak to stand up and do what was right. He wanted to study literature but was too weak to say so, and so studied it in secret on his own time. His small kindnesses to the women made him that much worse, because at least no one expected his brother or father to be kind at all.

The unrelenting brutality Poornima and Savitha endured really underscored how this is just the way it is for so many people, especially women, in so many parts of the world. It wasn’t so gratuitous that it was overdone, but it was an exhausting read. The end didn’t help, and I can see that it might be deeply unsatisfying to some readers. Personally, I thought it was perfect, because how could that particular scene be written ideally? I don’t think it can be, but the promise of it has to be enough. I do think Savitha was opening the door, and I do think it was ultimately a hopeful ending. The story at the beginning, with the old woman tending the trees that she called her daughters, seems to me to be foreshadowing of the end, that the women are strong enough to endure anything. Same with the owl’s story and how, if two people want to be together, they’ll find a way to do it. Poornima’s and Savitha’s friendship transcends anything they had endured, and for them not to find each other is not to be considered. I do choose to be hopeful at the end of the story.

Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows

Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows  Persepolis

Persepolis

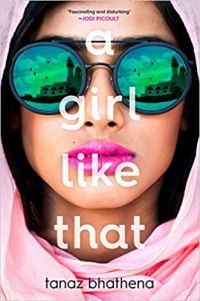

A Girl Like That

A Girl Like That  We Should All Be Feminists

We Should All Be Feminists