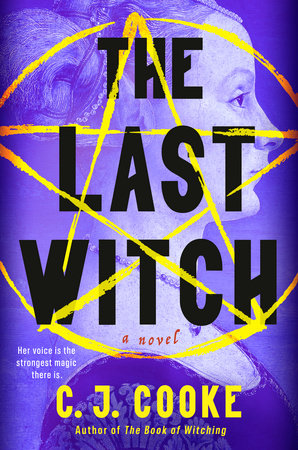

CJ Cooke’s latest novel, The Last Witch, takes readers to late medieval Austria and one of the most infamous witch trials of the era, the Innsbruck trial of 1485. Helena Scheuberin, a sometimes recklessly outspoken woman, finds herself accused of witchcraft after publicly defending another woman who had been unjustly executed. Unfortunately for Helena, the man she yelled at/ publicly chastised/ embarrassed/ expressed an opinion to was none other than Heinrich Kramer, the Dominican inquisitor and author of the notorious Malleus Maleficarum, a vile and influential treatise that helped fuel Europe’s witch persecutions for centuries. From the moment Helena crosses him, her arrest for witchcraft is all but guaranteed. She and several other women are imprisoned, forced to navigate between survival and surrender in a world ruled by fear, superstition, and male authority.

Cooke’s novel is an immersive, richly imagined, deeply researched recreation of the Innsbruck trial. She brings to life both the horror of the accusations and the humanity of the women ensnared by them. The depiction of Helena’s imprisonment is particularly vivid. Cooke spares no detail in describing the cold, dark dungeon, the stench of decay and rot, and the absolute terror that permeates its atmosphere. The scene with the thumbscrews is enough to upset the stomach. And if you think thumbscrews aren’t too bad, other than the agony it causes, consider that most people who endured it never had the use of their hands again, if they survived at all and didn’t die of septic infection instead.

Despite all the misery depicted, the novel finds many moments of solidarity and resistance among the women. There are whispered prayers, a shoulder to lean on, a hand to hold, just a bunch of small kindnesses and defiances that help the women hold on to their dignity. Cooke’s attention to historical texture really helps to sell the oppressive atmosphere of a world where accusation itself could easily be a death sentence. She makes the world tangible and immediate, and brings historical suffering to life without losing compassion.

Helena Scheuberin was a real historical figure, and she emerges here as a woman of great courage and intelligence. She is deeply human and quietly heroic, someone who refuses to let terror erase her voice. Cooke’s portrayal emphasizes her wit, compassion, and sense of justice, showing a mind capable of challenging the warped logic of her accusers. Through Helena, Cooke gives voice to the countless women silenced by history, transforming a name in a court record into a fully realized person whose story resonates across centuries. She is someone I think I would have liked to know in real life. She’s principled, brave, and unwilling to accept the world’s injustices without question.

Heinrich Kramer, too, was a real person, to the eternal horror of anyone with an actual conscience. Cooke’s depiction of him is actually enraging. Not because of her choices as a writer, but because of the man himself. He is not the kind of villain you love to hate; he is a man whose arrogance and cruelty provoke genuine loathing. Knowing his historical role makes him even harder to stomach within the novel. This was a man whose Malleus Maleficarum codified misogyny into doctrine and justified the murder of innocent women under the guise of piety. Modern commentators have aptly called Kramer a “medieval incel,” and Cooke captures that description perfectly. He’s an insecure, petty, self-righteous man driven by resentment and fanaticism. Other characters are put off by him and his appearance, which is scrawny and filthy. Apparently being dirty and stinky is how one shows one’s devotion? Gross. Pretty sure Jesus took a bath once in a while. Baptism is at least good for something. Cooke’s portrayal of Kramer as both pathetic and terrifying is one of the book’s strengths and really highlights how personal bitterness and institutional power can combine to create monstrous people doing monstrous deeds.

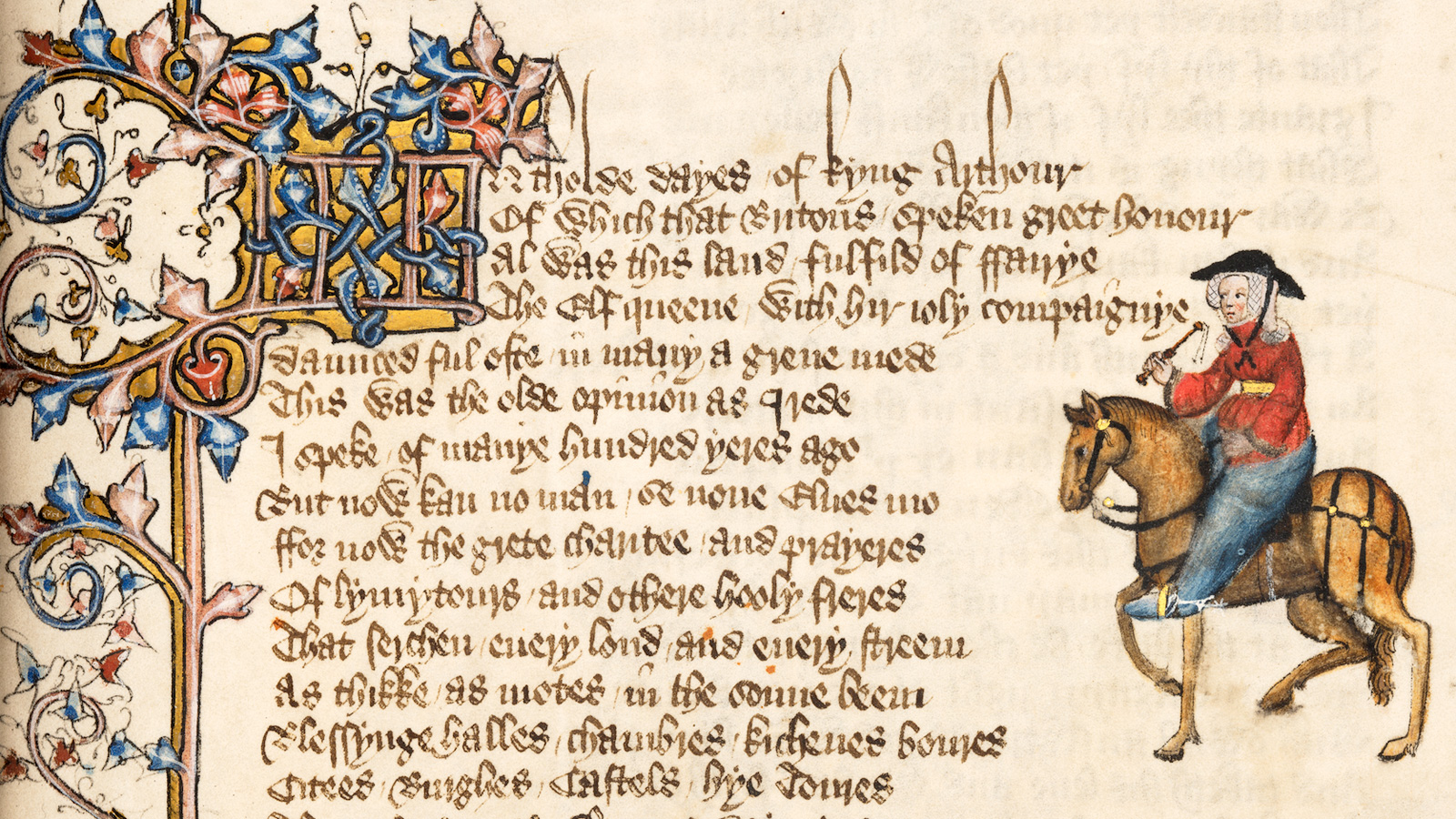

I loved this novel for its exploration of loyalty, courage, and the power of words. Helena never falters in her loyalty to her fellow prisoners. Cooke shows that bravery can come in many forms – sometimes it’s loud and defiant, sometimes it’s quiet and persistent. One of my favorite scenes was when the women in the dungeon taught each another how to pronounce their names correctly. That’s a small act that reclaims their humanity but it’s also a reminder that words are magic. That idea is borne out by the second-most common definition of the word: “a spoken word or form of words held to have magic power” (“Spell”). It’s bitterly ironic that Kramer’s use of the word “witch” becomes his own dark spell, a verbal act that destroys lives as surely as the fire he wants to burn them with. As the saying goes, I’m not afraid of witches, I’m afraid of the people who want to burn other human beings alive.

And finally, there’s the dedication, which I adore: “To Gisèle Pelicot.” YES, witch! A perfect nod to resistance and reclamation.

The Last Witch is an engrossing, haunting, and beautifully written novel that revives a real woman’s story with empathy and power. Cooke transforms historical tragedy into a testament to courage, and I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Reference:

“Spell.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spell

The Witches Are Coming

The Witches Are Coming  The Power

The Power