Of all the Queens throughout British history, one of the most infamous surely must be Anne Boleyn (c. 1501 – May 19, 1536). Painted throughout history as a temptress, seductress, traitor, and worse, Anne Boleyn has gotten a seriously bad rap. But where does this image of her really come from? Was she really these things? The answer is probably no, not really. Possibly the truth is somewhere in the middle, or maybe we will never know the truth at all. Many historical novelists have had their own interpretations of Anne over the years, and depending on their perceptions, readers are presented with very different people.

A very quick history lesson:

- Much of our basis for how we view Anne Boleyn comes from the letters and documents of Eustace Chapuys, the ambassador for the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

- Chapuys’s job was literally to report what he heard at Henry VIII’s court, including about Anne, much of which came from her enemies. His actual letters reported others’ words, not necessarily his own.

- The Holy Roman Emperor was Catherine of Aragon’s nephew, so he was naturally inclined to dislike Anne based on her replacement and treatment of his aunt. Often, he referred to Anne as “the Concubine,” which was recorded in letters to and from Chapuys.

- Chapuys didn’t like Protestants or the French. At all. Anne was both Protestant and had French mannerisms, so it’s easy to see why historians think he hated her.

- Chapuys and another man, Pedro Ortiz, exchanged a lot of letters in the course of their duties and the two might have become conflated over time. Ortiz was Catherine of Aragon’s proctor in Rome. HE REALLY loathed Anne, and his letters do actually prove it. Chapuys’s letters are fairly unbiased.

- Chapuys only met Anne once, in April of 1535. All his other information about her came from other sources, including her enemies.

- Chapuys was one of the only people who publicly stated that he thought Anne was innocent of the charges brought against her and was a victim of political machinations.

- Regardless of politics, Anne was unpopular. Her failure to have a son gave Henry VIII the impetus he was looking for to have Thomas Cromwell charge her with adultery, incest, and treason.

- Adultery, when one is married to the king, is high treason, punishable by death.

- Five other men were charged with Anne and executed.

One scene that is often seized upon by authors occurs during Anne’s tenure in the Tower. While she was held in the Tower, both before and after her trial and sentencing, she was attended by Mary Kingston, the wife of the Tower constable, Sir William Kingston. The conversations Sir William recorded and reported to Cromwell were used at that time to seal Anne’s fate, as well as that of the five other men who were executed with her. Today, Kingston’s letters are considered among the most important bits of evidence that Anne and the others were totally innocent. In a letter written May 19, 1536, the morning of Anne’s execution, Kingston wrote:

This morning she sent for me, that I might be with her at such time as she received the good Lord, to the intent I should hear her speak as touching her innocency alway to be clear. And in the writing of this she sent for me, and at my coming she said, ‘Mr. Kingston, I hear I shall not die afore noon, and I am very sorry therefore, for I thought to be dead by this time and past my pain.’ I told her it should be no pain, it was so little. And then she said, ‘I heard say the executioner was very good, and I have a little neck,’ and then put her hands about it, laughing heartily. I have seen many men and also women executed, and that they have been in great sorrow, and to my knowledge this lady has much joy in death. Sir, her almoner is continually with her, and had been since two o’clock after midnight.

This statement serves as the focal point for many interpretations of Anne’s behavior in various novel, TV, and film adaptations. On a surface reading of Kingston’s letter, we might assume that he thought her actions to be aberrant, considering that he noted other condemned prisoners had displayed “great sorrow” at their impending demise, but Anne instead had “much joy in death.” However, a closer look indicates that he isn’t actually offering a commentary on Anne’s state of mind. He is merely observing what his charge is doing, as his job requires, like a doctor charts a patient’s progress. There is no judgment in Kingston’s letter. To the contrary, the letter implies he is a compassionate jailer. He attempts to calm her fears about any pain she will face during her execution, which he didn’t have to do. Perhaps he was kind to her because he believed she was innocent. We may never know, but writers certainly have their views on the matter. Two popular historical novelists, Margaret George and Alison Weir, have each tackled this scene, with very different results.

In Margaret George’s novel The Autobiography of Henry VIII, the scene in the Tower is unsettling to Kingston, who is distracted by preparations he must oversee for the executions. Kingston is on the verge of exhaustion, frazzled by the multitude of administrative functions he has to fulfill, and is perturbed by the lack of instructions from Henry VIII about Anne’s coffin. “Dawn came before five, and Master Kingston was already exhausted from the tasks of the day ahead. …[H]e naturally had many details of both practicality and protocol to attend to. … He was running late. … But still no word about the coffin!” (George 542). Kingston, when he goes to Anne’s rooms to deliver news of her delayed execution, is relieved by it because it gives him more time to carry out his other duties. When he speaks to Anne, he’s obviously in two places at once and has to force himself to pay attention to her. When she speaks, Anne’s dialogue is consistent with Kingston’s description in his letter to the king. Upon learning of the delay, Ms. George describes Anne as disappointed and sad. Anne goes on to comment that she thought by noon to be past her pain. But then she grabs Kingston’s arm and whispers frantically to him that she is innocent. Abruptly, she has another mood swing and asks him fearfully if her death will be painful. Her volatile swings in mood make her seem mentally unstable, which at that time in history would also imply her guilt. This version of Anne is worried about how big the executioner’s axe is: “I have a little neck. … But the axe is so thick, and rough” (George 542). Upon learning that she was to be beheaded by a swordsman, she laughed, saying that Henry was ever a good and gentle sovereign lord. That, friends, is what I like to call sarcasm. Her laugh is described as “that hideous, raucous laughter” (George 542), like a witch’s cackle, and Kingston is thoroughly unnerved by it. Anne’s laughter again starts up when she jokes to Kingston that she will be known as Queen Anne Lack-Head. Here, George describes Anne’s laughter as “shrieking” (543) and Kingston is actually frightened by it, all but fleeing her Tower chambers. The overtones of witchcraft, overlaid with her added comments about Henry making her a martyr, underscore the implied mental instability implicit in the text, neatly tying up the issue of her unsuitability to be queen. All told, her mannerisms combine to create a character that is unsympathetic, severing any lingering tender feelings readers may have had for her. Given that this novel is told from Henry’s perspective, it makes sense for Ms. George to make Boleyn a character that readers no longer like at this point. We are seeing her through his eyes, and by now, he truly believed that she was guilty and had wronged him grievously.

In Alison Weir’s novel, Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession, readers get another interpretation of Anne’s famous “little neck” comment. Right away, the novel has a decidedly favorable tone towards Anne, whereas George’s novel did not. From the moment Anne arrives at the Tower, concessions are made to her rank as queen: She was given the same rooms she had used before her coronation, she had several ladies attending her, she ate with Sir William and his family. Her clothes were richly described, and pomp and ceremony were seen to more so than in other novels. Kingston is referred to as the “Gentleman Jailer” (Weir 527), making him sound as though he is a courtier there to wait upon her and lending more dignity to Anne’s imprisonment than it would have had otherwise. After her sentencing, Kingston was more forthcoming with Anne and was very gentle, taking time to talk with her and answer any questions she asked of him, acting very much the gentleman indeed. When he informed Anne of the time of her execution, she was relieved, for she had just been forced at Henry’s order to watch from the Tower the executions of the other five men. Kingston showed no hint that her relief was aberrant, as in other interpretations. Here, Anne is described as “agitated and panicky” (539) when her execution is delayed. This seems the more natural reaction in the two novels. Who among us hasn’t been agitated and panicky over facing something that we are dreading and have no choice to go through with? Hysteria and inappropriate reactions seem the most logical explanation. Anne has spent days dwelling on the fact that she’s going to die by having her head cut off. She is asking a normal question to a person who is a logical choice, having witnessed many executions in his line of work. Anne says, as we know, that she had hoped to be past her pain, because she’s been brooding about it and the suspense is eating her alive. Kingston is quick to reassure her it will be painless. When Anne says, “I have heard you say the executioner is very good, and I have a little neck” (593) she gives a nervous laugh afterwards. Of course she is nervous. She’s beyond nervous; she’s petrified. But she is also acknowledging Kingston’s role as a figure who has given her succor, because he was the one who told her about the swordsman from Calais, and that he was skilled and humane. Kingston went out of his way to try to calm her, without judgment. She explains to him that she wants to die now but her body “shrinks from it, so I am heartily glad it will be over quickly” (540) and Kingston assures her it will be, and squeezes her hand kindly. This is a very human moment for both of them, the most poignant and touching of the entire book, to be honest. This is a woman who went from being a queen to taking comfort from the man who will lead her to her execution. More so than any other scene, this is truly the full circle moment for Anne.

There is a reason why novelists continue to write about the Tudors. Yes, in part it is because the books will sell. But more than that, there is still a deep current of compassion we feel towards the people then, a desire to understand their motives and thoughts, and to better understand ourselves through them. Anne Boleyn remains a tragic figure – hated by some, beloved by others, mysterious in many ways to all. Her story encompasses so much depth that it is hard to look away, regardless of how one views her. Nearly 500 years after her death, the lingering controversy, intrigue, and curiosity surrounding Anne Boleyn may be the best elegy she could have asked for.

References:

Bordo, S. (2012, May 6). When fictionalized facts matter. The Chronicle Review, retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/When-Fictionalized-Facts/131759

George, M. (1987). The Autobiography of Henry VIII, With Notes by His Fool, Will Somers. St. Martin’s Griffin: New York.

Mantel, H. (2012, May 11). Anne Boleyn: witch, bitch, temptress, feminist. The Guardian, retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/may/11/hilary-mantel-on-anne-boleyn

Mantel, H. (2012). Bring Up the Bodies. Henry Holt and Co: New York.

McKay, L. (2016, May 6). Did Eustace Chapuys really despise Anne Boleyn? HistoryExtra.com, retrieved from https://www.historyextra.com/period/tudor/did-eustace-chapuys-really-despise-anne-boleyn/

Weir, A. (2017). Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession. Ballantine Books, New York.

The Land Beyond the Sea

The Land Beyond the Sea  Sea Witch by Helen Hollick. The first in the Sea Witch series featuring fictional pirate Jesamiah Acorne. Hollick’s research be impeccable and many other real life pirates have roles in these tales. This high seas rollicking adventure makes it easy to see why pirates be romanticized so often.

Sea Witch by Helen Hollick. The first in the Sea Witch series featuring fictional pirate Jesamiah Acorne. Hollick’s research be impeccable and many other real life pirates have roles in these tales. This high seas rollicking adventure makes it easy to see why pirates be romanticized so often. Hook’s Tale: Being the Account of an Unjustly Villainized Pirate Written by Himself by John Leonard Pielmeier. As the title suggests, this be the autobiography of the illustrious, dashing Hook himself.

Hook’s Tale: Being the Account of an Unjustly Villainized Pirate Written by Himself by John Leonard Pielmeier. As the title suggests, this be the autobiography of the illustrious, dashing Hook himself.  Daughter of the Pirate King by Tricia Levenseller. A 17-year-old pirate captain allows herself to be captured so that she can search her enemy’s ship for a secret map to a hidden treasure. A true pirate will go to any length to seek treasure and adventure.

Daughter of the Pirate King by Tricia Levenseller. A 17-year-old pirate captain allows herself to be captured so that she can search her enemy’s ship for a secret map to a hidden treasure. A true pirate will go to any length to seek treasure and adventure. Under the Black Flag by David Cordingly. Written by the former head of exhibitions at the British National Maritime Museum, this novel be all about the fact and fiction of a pirate’s life. Yo ho, yo ho, a pirate’s life for me…

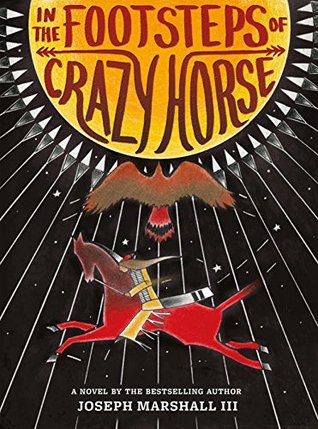

Under the Black Flag by David Cordingly. Written by the former head of exhibitions at the British National Maritime Museum, this novel be all about the fact and fiction of a pirate’s life. Yo ho, yo ho, a pirate’s life for me… In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse

In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse  The History of William Marshal

The History of William Marshal